Hungarian merger control is generally aligned with the relevant EU rules with only relatively minor exceptions or special rules. For example, a notable special rule – which follows similar trends in major European jurisdictions – is the existence of the soft threshold regime, which enables the Hungarian Competition Authority (the Gazdasági Versenyhivatal, “GVH”) to intervene in case the traditional/“hard” thresholds are not met, but where competition is threatened on a specific market (eg in case of “killer acquisitions”).

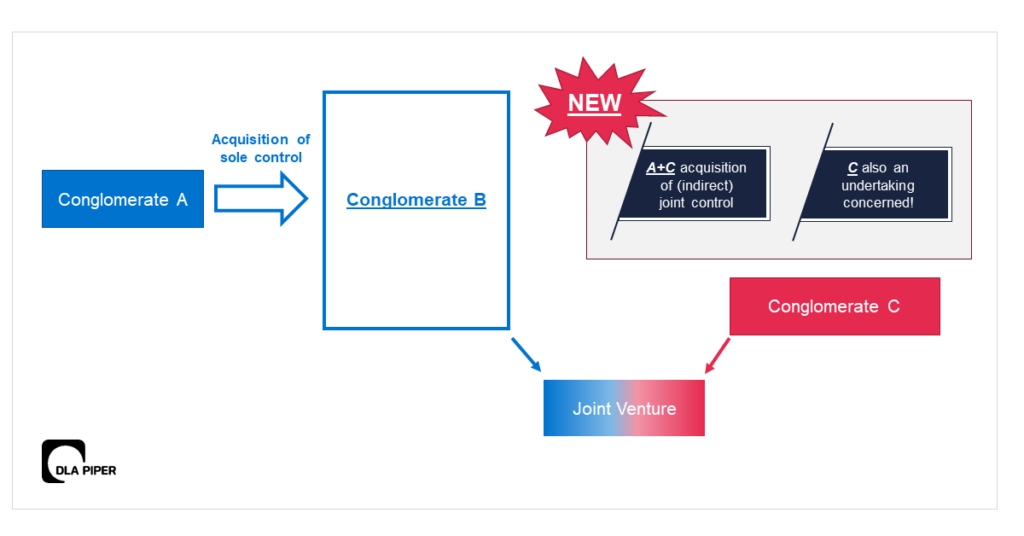

Now, recently, a further important exception has arisen, which diverges from the approach taken by EU merger control and which has important ramifications for all transactions potentially falling under Hungarian jurisdiction (ie typically those, where the EUMR thresholds are not met, that is those transactions, which do not fall under the one stop shop jurisdiction of the European Commission). Namely, if a transaction involves a target company group, which has a joint venture with a third party, then the GVH considers this – fully independent – third party also as an “undertaking concerned” by the concentration (even though the third party typically plays a passive role in the transaction, in some cases not even being aware of its existence). For example, if Conglomerate A acquires sole control over the entire Conglomerate B and Conglomerate B has (among lots of other companies) a joint venture (JV) with Conglomerate C, then the GVH’s view is that we talk of two related transactions: (i) an acquisition of sole control by A over B and (ii) an acquisition of joint control (indirectly) by A and C over the JV. As a result, the GVH also requests this second transaction to be fully assessed and explored in the notification as a “follow-on merger”.

Importantly, this approach has now been expressly confirmed in the recently published Vj-43/2020 (GI International case) decision, where a HUF 11.1 million fine was also imposed for gun-jumping (although literally, the GVH’s merger notice included this possibility since 2021, parties have questioned such strict interpretation in several cases, but any uncertainly has now been dispelled).

Although the above issue may appear to be rather technical at first, it has major procedural and substantive consequences for the mergers of all larger conglomerates/company groups, which typically include some joint venture companies, which are controlled jointly by the given conglomerate and a third party.

First, when calculating the turnover of the conglomerate/company group, the traditional approach (under the EUMR and under the merger rules of most jurisdictions) would simply dictate that one takes into account a half of the turnover of the JV (in case of two joint controllers) and then proceed with the turnover calculation, not looking at the other joint controller at all. Now, under the GVH’s new approach, the other joint controller is a “fully-fledged” undertaking concerned, which means that its turnover (including its entire group of undertakings!) is relevant from the perspective of turnover calculation. This can entail that in case a “larger” company acquires a “smaller” company, then – if the “smaller” company has a JV with another “large” company – there would be an obligation to notify in Hungary, even if originally the turnover thresholds would not be reached as the “smaller” company’s turnover fell below the HUF 1 billion threshold.

Second, treating the third party as an undertaking concerned also requires additional efforts by the notifying party: it has to present this third party (ie its entire group of undertakings) in the notification form (in detail, including the activities of all subsidiaries). This is especially curious, since the third party is not in any way a participant to the original transaction that is notified to the GVH (as it is merely a passive observer, merely following the change of ownership in a JV, in which it participates). This can also entail significant practical challenges in terms of data gathering as well.

Finally, the third party’s involvement may also change (or at least refine) the substantive assessment of the transaction’s notification as one has to take into account each market where the third party is active in. This could be fully understandable in case the notifying party and the third party are direct competitors (as indeed, there could be horizontal issues stemming from the fact that the transaction would result in competitors sitting on the board of the JV). At the same time, the GVH’s new approach could cause additional hurdles in case the horizontal or vertical “overlaps” exist between the activities of the notifying party and those “parts” of the third party that are far removed from the JV itself.

As a result, parties looking at the Hungarian merger control notification obligation should be well aware of the above new exception and should tailor any merger control information requests accordingly to avoid any gun-jumping allegations (and thus: possible fines) in Hungary.

Authors

Gábor Fejes

Gábor Fejes

Zoltán Marosi

Co-Head of Competition and Antitrust

Zoltán Marosi

Levente Molnár

Competition and Antitrust

Levente Molnár

How can we help? Get in touch.

Follow us on LinkedIn

Subscribe to our newsletter to be among the first to know about our news and articles as well as business event invitations!